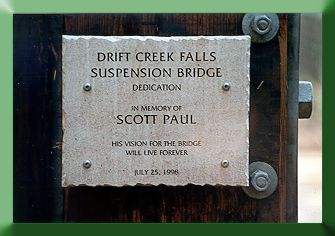

DRIFT CREEK BRIDGE

DEDICATION

Memorializing Scott Paul

25 July, 1998

Carroll Vogel Remarks

Bridges and trails are a metaphor for the human experience. They carry us across seemingly impossible terrain and bring worlds together. Trails, like the continuum of our lives, carry us to and through the great diversity of the earth. Old growth forest, sub-alpine meadow, storm-lashed shore; all linked by trails that rest on the landscape like pathways through time. And the bridges, especially backcountry bridges, allow us to vault chasms that divide, permitting us to experience worlds that seem near enough to touch, but impossible to attain. Simple in form and function, with a singleness of purpose unchanged since the dawn of human history when primitive humans opportunistically traversed a fallen log to reach new land, fresh opportunity. It is no wonder that bridges have come to symbolize human aspirations and folly, and a few to represent some of the greatest achievements of human engineering endeavor.

Bridges remind us of what it means to be human, to be perpetually reaching out for unachievable objectives, to dream, but to dream our dreams in the reality of the present, while fully awake. Great bridges are grand engineering and architectural masterpieces and building them is amongst the most challenging of construction endeavors. Joseph Strauss, the builder of the Golden Gate Bridge, once proclaimed: Building a bridge is like having a war with the elements of nature. Nowhere was that more relevant than here at Drift Creek. To that truism I would add that bridge building represents nothing less than a triumph of the human spirit.

In the middle 1800s John Augustus Roebling conceived of a great bridge to span the East River in New York. John Roebling was the premier American Bridge builder of his time, a pioneer in the design and construction of suspension bridges, and the inventor of wire rope. The bridge he envisioned would be the greatest cable bridge in the world and, over the course of a dozen years, he meticulously worked out every aspect, every detail of his great structure. Unfortunately, in 1869, Roebling had his foot crushed by a ferryboat as he surveyed a location for his great bridge; within three weeks he was dead of tetanus. Ground on the project had not yet been broken.

Many thought that Roebling's vision of a grand bridge across the East River would die with him. But the torch was passed to his son Washington, then 32 years of age. Despite his youth, young Roebling was undaunted, and so he pressed ahead determined to see his father's vision realized. Three years into the project the abutments had yet to emerge from the earth when Washington Roebling developed caisson's disease. Caisson's disease is similar to the bends suffered by divers, and is a hazard associated with work in the pressurized chambers used for excavating the bridge footings to depth below water level. His affliction left him scarcely able to see, write, or walk.

By then of course, the doomsayers were legion, and it was believed by many that the project was ill-conceived, ill-fated, and impossible to complete. But the Roeblings were a resolute bunch. They were Bridge builders above all else, and so another Roebling stepped forward: Washington's wife, 29-year old Emily. For nine years this remarkable woman was the intermediary between her ailing husband and the great project; she was his eyes, his voice, his hands, until all the work was finished.

Fourteen years in construction; beleaguered and beset by challenges at every turn, tempered by tragedy, the Brooklyn Bridge is regarded by many to be a superlative engineering and architectural achievement of the industrial age. It is unquestionably a triumph of the human spirit.

Much the same can be said of the bridge over Drift Creek. Though separated by the geography of a continent, and a quantum leap apart in scale and scope, they are figurative brothers in human terms. Both bridges were visited by tragedy and lost their grand visionary. And both were completed when many thought it could not be done. Today, they stand as a legacy of the vision of those men who dreamed them into reality but never saw the tangible fruit of that vision; a legacy for the enjoyment of countless generations.

I first met Scott Paul about 1986. We were contemporaries, trail builders who had found an adopted home in the Northwest and taken up roots much like the giant trees that surrounded us. Scott came across a continent to find these mountains while I traveled an ocean. For us both the world we found here captured us fully heart, mind and body. Scott worked for the Forest Service and when I came to know him best he ran the trails and wilderness program for the Mt. Baker Ranger District, Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, WA. At the time I was a contractor working with the agency to develop training programs for the teaching of trail and bridge building skills. I'm here to tell you that we didn't know what to make of each other at first.

Passionate, irascible, bull-headed, independent, irreverent, determined, skeptical of authority, obsessed with history, and driven by romantic notions of traditional work skills, the wild west, our mission in life and our place in the world around us. These were the qualities we saw in one another, like looking in a mirror but finding an image other than your own. Once we got past the shock of recognition ours was a relationship of deep mutual respect and shared passion. Some, I think, saw a measure of competition, but not unlike that between siblings. Over the years a number of significant projects brought us together and I came increasingly to the realization that we were more alike than not. Scott hosted my training programs, and I later contracted to build several major trail projects on his District.

The opportunity to become the best of friends seemed to elude us however, as we were perpetually so busy. But always we shared a love for our work, for trailbuilding, and especially for bridges. I think often of the time about five years ago that Scott hailed me at the Ranger Station one day as I stopped in. "Carroll, come and see the plans!" The plans were those for Drift Creek Bridge and, it is fair to say, we devoured them. We looked at every detail, every design element. We strategized on erection methods and assembly procedures, and we waxed eloquent on the symbolism of building such a grand bridge over the precipitous canyon at Drift Creek. Scott Paul was consumed with passion for this project. It burned like a fire inside him.

Later, returning home one weekend from trailbuilding high on Mt. Baker, I received the stunning news that Scott had left us here to carry on building trails and bridges without him. As with most imponderables, the loss of a kindred spirit gives pause for reflection. With Scott's passing I felt the tangible absence of a rare person that understood implicitly the relevance of my own world. Our paths through this life parallel, but similar, our temperaments more alike than not. Later I learned another thing we shared: the year of the horse. Our birthdays in June of 1954, two days and an ocean apart; like twin sons of different mothers.

After the accident, there were those in the Forest Service who, like the Roeblings, would not let Scott's vision for a great bridge be squandered by tragedy. They persisted in pursuing his dream and soon enough I seized an opportunity to join them. Picking up where Scott left off was no small task.

Not a day went by but that Scott was on our minds. He was like an invisible but less than silent member of the crew. Omnipresent. Encouraging, cajoling, extolling his grand plan, applauding our successes, mocking us when our spirits were down, shredded by the elements or technical difficulties. Close your eyes: Those of you who knew that voice can surely hear it now. Some days, when our spirits were thoroughly depleted by the interminable iron gray sky and endless quagmire of sucking mud, Scott's voice was strongest. Come on you floggers, we're gonna get this done! Once the towers were up, I often imagined them as his perch, the world of Drift Creek entirely within his purview. Like the resolute Henry Stamper in Ken Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion: Never Give A Inch, he seemed to say, just by being there. Once begun, there was no way for us to contemplate failure.

And so it came to be that today we can all travel a

pathway through the forest canopy, high above Drift Creek, buoyed by Scott's

inspiration. When you make that journey

do not doubt that Scott is there, awaiting your visit. He is present in the laughter of children as

they scamper forth above the canyon. And

in the gasp of awe when adults who are children yet step away from the cliff

and observe the world beneath their feet tumbling away to airiness and mist;

only the bridge between them and the great unknown.

And so it came to be that today we can all travel a

pathway through the forest canopy, high above Drift Creek, buoyed by Scott's

inspiration. When you make that journey

do not doubt that Scott is there, awaiting your visit. He is present in the laughter of children as

they scamper forth above the canyon. And

in the gasp of awe when adults who are children yet step away from the cliff

and observe the world beneath their feet tumbling away to airiness and mist;

only the bridge between them and the great unknown.

Scott's was a life sustained by wild places and a love for the paths that made them accessible. He was a poet, a student of history, and a teacher of traditional work skills. He was a dreamer whose creative energy elevated trailbuilding to an art form, an expression of his vision in concert with the wildland environment. He both inspired and drove people crazy with his passion, determination, and fantastical ideas. His mark is a legacy of enjoyment and wonder for generations to come and his spirit lives today among his loving family, and a legion of trail builders for whom he was an inspiration, mentor, and friend.

Carroll Vogel

Seattle, Washington

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PRIOR TO FORMAL REMARKS

Despite how it seemed at times, I did not build this bridge alone. Prior to beginning my formal remarks some acknowledgements are in order.

Janet Paul, Jerry Carlson and especially Charlie Warren: The most patient and best USFS triumvirate I have ever worked with.

Fred Wright: The engineer of record who was extraordinarily gracious in receiving and reviewing our numerous suggestions for improvements and design modifications.

Al "Mike" Highberger: My engineer, business partner, and father.

Scott Paul's family: Especially Deb Paul, who strove to maintain perspective when the future of the project hung in the balance.

And most especially my crew:

Jim Lemieux, Russ Dalton, Scott Matthew and Lu Lemieux: All of whom had worked previously for Scott Paul.

Robert Mitton: My machinist and a genious of a fabricator.

Kevin Monohan, Keith Jellerson, and Ry Koteen: Reinforcements who helped with the big push.

Kim Vogel: My sister, who was always there to help when others were not, and who also brought a crew along with her, namely...

Bryce and Austin Thompson: My nephews, the next generation of bridge builders in our family.

Keith Monohan: My right hand man; the best there is and one young man I'd be proud to have as a son.

And Jennifer Knauer: My partner, who understands how solitary life with a bridge builder can be.

Carroll Vogel

July, 1998